A Tribute to my Dad

Gentle readers. I have lost my Dad, and my heart is raw from the losing. I have been trying to start a blog post on other topics, but I just can’t get through one until I’ve written a post dedicated to Dad. But I have a problem: how can I memorialize such an important man’s life adequately in one blog post?

So here’s a heads-up for you, gentle readers: this post may only interest me, but I must muddle through it.

Here’s Dad, sharing the crumbs from his rhubarb crisp with our orphaned baby squirrel, Tommy.

Dad was a farm kid.

Dad–James, or Jimmy Lee (his mother called him this) or most often, just Jim–was raised on a dairy farm near Ellis, Nebraska. He grew up with an older brother, Harry, the handsome “Golden Boy” and the apple of their dad’s eye (Dad’s words), and a cute younger sister, Helen. Dad grew up working on the farm whenever he was at home. He wasn’t allowed to go out for any after-school activities or sports, because his folks needed him at home.

Dad would tell me how my Grandpa taught Harry how to drive the tractor and the combines, as Grandpa apparently thought Harry would eventually take over the farm. Dad was the fix-it kid, the builder. There was a board pile out on the farm, where Grandpa tossed odd pieces of wood and whatnot. Whenever Grandpa needed something built or fixed, he’d send Dad to the board pile.

Whether Dad’s acumen in building, designing, or fixing just about anything, was apparent to my Grandpa from an early age (surely it was?) or whether the constant trips to the board pile served to develop these talents, I don’t know. (Which came first?) But he certainly developed those talents well.

Dad liked farming and hoped to step into running the farm when his dad retired, especially since Harry decided to go to college and pursue a career away from the farm. Things didn’t turn out that way, however. I’m guessing that communication wasn’t my Grandpa’s strong suit. Dad graduated from high school and went straight into the army for a few years. When he returned home, he discovered that Grandpa had sold most of the farm.

This was a big surprise, and a crushing disappointment to Dad, and he had to pivot quickly. He decided to go to the University in Lincoln to study Pharmacy. I often wonder how different our lives would have been, had he stepped into the dairy farming business, as was his original goal.

Though he had to change his plans from farming to Pharmacy, Dad always retained all the interests and fascination with growing things, raising animals, and other farm-related interests. Though we lived in town, he always owned tractors, a well-equipped wood shop, and grew huge vegetable gardens and orchards. He planted trees–including fruit trees–on every property he owned. “You don’t plant trees for yourself,” he’d say. “You plant them for the next generation.” But we ate a lot of fruit off those fruit trees, not to mention grape vines, berry brambles, etc. that Dad planted. Mom was right next to him, growing herbs, perennial crops like rhubarb, horseradish, and, of course, flowers.

When I was a kid, Dad bought an old house on a lot across the street from our house. We tore the house down, hauled it away, and Dad and Mom planted a huge garden and orchard on the empty lot.

And a pharmacist

I asked Dad once, why Pharmacy? He answered that he admired the Pharmacy in Beatrice, where his mother would shop. “The pharmacist always looked sharp and clean,” he said, “and the store was such a pleasant place to shop. It was a nice environment.” I think the compounding process of making medicines appealed to Dad, too. Back then, pharmacists were chemists, not just “pill counters,” as Dad later would note. Dad was sharp, with an excellent memory and a fine mind.

Dad met Mom while he was a student at UNL, and they were married a couple years later. They lived in Lincoln (coincidentally, only a few blocks from where some of our kids live today) for a few years, while Dad finished his education and then worked in drug stores there. His dream, however, was to buy a Pharmacy in a small town. He and Mom both believed that it was healthier and safer to raise children in a small town. Dad observed that in a small town, everybody watched your kids. It wasn’t just you. They were less apt to try to get away with things. In a city, kids could get into real trouble, said Dad, but it wasn’t easy to do the same in a small town.

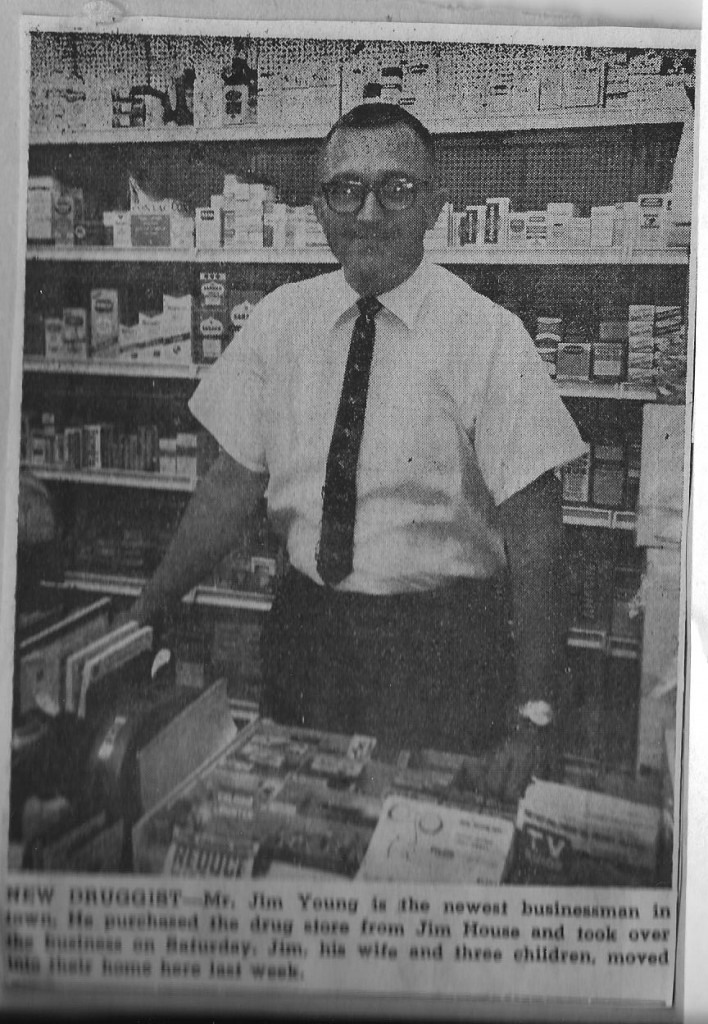

A drug store came up for sale in Nelson, Nebraska, a tiny town southwest of Lincoln, and Dad drove there to take a look. After meeting with Mr. House, the pharmacist, and examining the store, he met with the banker in town and bought the store and a huge fixer-upper house just a few blocks away, all on the same day.

(Every time I have a question, still, weeks after Dad died, I instinctively reach for my phone. I am that accustomed to asking Dad for clarification. “Dad, how much did our Nelson house cost? Was it $2500.00? or $1800.00?” but I’ll have to wait until I see him again in Heaven to ask. Although I doubt that it’ll matter much to me then.)

And so it happened that House’s Pharmacy became Young’s Pharmacy, a few months later. Dad did some creative sign-painting, so he didn’t have to re-paint the entire side of the building with the name of his store on it. From the start, we all referred to Dad’s new pharmacy as “The Store.” “Dad, are you going down to The Store?” or “I’m going to run to The Store for a minute”; etc. Dad’s new store was everything you could ever want in a small town corner drug store. It was sterotypical in the very best way. It was that small town gathering spot that every town used to have.

The front of Young’s Pharmacy had large plate glass windows, mirrored columns, and a mosaiac walkway that encouraged you to enter. Bells on the door made sure that everybody knew when you walked in. The floors were dark hardwood, oiled and then swept to have a nice well-worn, polished look. The clerks who worked at the store were always middle-aged to older women, often widows, who needed easy work and a steady paycheck. I think word got out that you had to have an old-fashioned name to work there too: Leona, Lillian, Loretta, Della, Emma, and Ruth were the names of the some of the store lady clerks. They became family to us. No Tiffanys, Brittanys, or Pattys applied.

At the back of the store was the element that clinched the deal for Dad to sign the dotted line. There sat the crowning jewel of every old time drug store in those days: the soda fountain. This one was a beauty, with a marble countertop, swivel barstools and two booths with red naugahyde fabric on the seats. For all the years that we lived there, there were at least two regular coffee groups every day that met whenever the store was open. Morning coffee met every day around 10:00–with the businessmen from town and occasionally a farmer or two, and afternoon coffee gathered around 3:00–with more farmers and maybe some retired folks. Everybody was welcome, of course.

Dad tried to sit down for a few minutes with the coffee groups when he could, but sometimes he was busy filling prescriptions or helping customers. A good cup of coffee costed 5¢ when he started the store, I think, and may have doubled to 10¢ eventually, much to the shock and bewilderment of the coffee drinkers! The cups that we used in the store were heavy diner cups; they probably held about 6 ounces, and Dad bought them from a King’s restaurant in Lincoln that went out of business.

(As a side note, I own two of these cups, and every time that Dad drank coffee at our house, he’d look for one of them.)

Schoolkids and other shoppers stopped in regularly for ice cream cones, malts, ice cream sundaes and cherry phosphates. You could order any type of combination of sodas and ice cream. I worked there in my teen years regularly, and some favorites were cherry Cokes, cherry phosphates, chocolate malts, root beer floats, and banana splits.

As long as I’m adding plenty of side notes: in his last few years, it was this community that I believe Dad missed the most. I can still see him, hunched over a paper napkin and pen, as he was drawing something that he was describing to the other men at coffee. (The regular groups were almost always comprised of men.) Or I would glance over to see all the men sitting motionless, listening, as Dad told a story or a joke. Waiting for the punchline. Dad would get to it, and the group would explode with laughter, settling back in their seats. Dad had a coffee group here in our current hometown, and I saw this same scenario play out again and again, although his coffee buddies here were closer to my age than his.

A maker and a fixer

As I mentioned above, there very nearly wasn’t anything that Dad couldn’t make or repair. When I was a kid, I remember people bringing watches with broken straps, necklaces with busted clasps, and other small items to him to repair. He had a set of little tools that he’d pull out and repair whatever he could. He had endless patience with that sort of thing.

Later, when I was an adult, if he saw me struggling with something—a low tire, a dull knife, a headache, whatever–he did what he could to fix it. And I wish I had a nickle for every time he came to rescue me, when I’d end up away from home with a flat tire, a dead engine, or something else. He was always so joyful to do this. One time Bryan and I we were traveling from our home in Iowa back home to Nebraska, and the engine in our ancient minivan died. We had to leave the van in a service station in the middle of Iowa. Dad rented a large van (our family was quite large already) and drove to Iowa to pick us up. It made him so happy to feel needed.

His buddies in town leaned on him for help in fixing and making things. He had a reputation for being able to figure out just about anything. (Except for his cell phone and his computer, which drove him crazy. But that’s what grandsons are for!)

Probably just about everybody who knew Dad owned something that he made or repaired for them. In his later years, he made hundreds of rolling pins for my blog shop, and had started making tulips out of wood, using his lathe and a brain-bending technique that he spent days studying. He had several puzzles that he had made, including one with a wooden arrow going through a wine bottle, that he loved to show people. “How do you suppose I made this?” he’d ask, and enjoy their attempts to explain how he did it.

Dad was so talented with his hands. Even into his nineties, his hands were steady and sure. And he was happiest when he was puzzling out how to make something new, or repair something in his shop. Even as he got more uncertain on his feet, he’d brave the cracked sidewalk that led down to his shop, for the pleasure that working in his shop gave him. (By the way, he built the shop when he turned eighty, I believe, because his old shop was beginning to fall apart from age. His new shop was huge, well-lit, heated with two heat sources, and beautifully organized.)

Dad used an old ax handle to work his apple cider press. He never felt comfortable letting anybody else operate it. It is not, shall we say, OSHA-approved.

A sharp mind

When I was a little girl and Dad and I were in the car together, to keep my mind off the horrible tendency to carsickness that I was cursed with, I’d ask Dad to talk about things. He knew something about everything, it seemed. “Dad, tell me about birds,” I’d say, and he would think for a moment, and then tell me everything he knew about birds. He would point out the birds flying in a “v” formation and explain to me why they did so. He’d explain why the blue jay’s call sounded like “Thief!” He seemed to have a steady recall of everything he’d ever read or learned, where he had read it, or from whom he learned it. The hours would fly by and, with any luck, my lunch would stay in my stomach where it belonged. “Tell me about rocks,” “Tell me about Abraham Lincoln,” “Tell me about bridges.”

I wish I would have been a better listener, and I wish I had my dad’s excellent recall for these precious times. But Dad would go into so much detail that my mind would inevitably wander. Good thing he didn’t ask me to regurgitate what he had told me! But I learned plenty, even if he usually shared more than I could absorb. Mostly I learned from Dad that you never, ever stop learning, and that the world is a fascinating place.

Here’s my cute dad, with a ball of pefferneuse dough.

A generous giver

Two of my most precious possessions at the moment are two knives that Dad gave me just a few weeks before he died. One day he watched me (painfully, I’m sure) struggle to cut up a watermelon with my chef’s knife, which had gotten quite dull. Within a few days, he walked in to my kitchen with a trim little box in his hand. He handed it to me. “Try that, sis, and tell me how you like it.” It was a very nice Chef’s knife, smaller than mine, and wickedly sharp. I’ve used it nearly every day since he gave it to me, and I think of Dad every time I use it. One day he asked me how I liked it. “It’s my favorite, Dad! I use it every day!” I’m glad I had the time to tell him that.

Dad was knowledgeable about sharpening knives, and would even carry his sharpening equipment out to our place occasionally and sharpen my knives for me.

I also had a little gardening knife that Dad had given me years ago. It was made in New Zealand, and had a yellow plastic handle. I used to carry it in my garden belt with my snips, and used it constantly. Somehow it fell out of my belt, and it is lost somewhere in the flower beds or my hoophouses. It’ll hopefully turn up someday, rusted and crusty with mud, alas. I moaned to Dad that I had lost that dandy little knife that he gave me.

A few days later, he handed me a little box. Inside was the same knife, only he had removed the cheap plastic handle and had made a handle of bone. It is absolutely beautiful. I will not be carrying it in my toolbelt, gentle reader. I don’t want to take any chance that I will lose it.

In his pharmacist days, the store was open 6 days a week, from 8:00 to 6:00, I believe. But Dad was continually being called to meet somebody at the store, because they forgot about getting a prescription filled, or something. He always dropped what he was doing, and would walk the 3 or 4 blocks down the the store, to help. He often delivered prescriptions to people who were too sick to go out. I know he wasn’t paid many times for prescriptions or store items, by people who were “hard on their luck” as he would say, and he would let it go. He was a generous man.

My sister Mollie and me, embarrassing Dad in the coffee shop on his birthday.

A Fine Life

I had never really thought about this before, but I think you can tell a lot about the way a person lived his life by who shows up to his funeral.

For all his talents and abilities, Dad was a very humble man. He was so talented making things out of wood in his shop, but he called himself, humorously, a “wood butcher.” Until the last few years of his life he was a curious and accomplished cook, famous for his tapioca pudding, barbecued ribs, chili, peppernuts, and most of all, his exceptional potato salad, among other things. But he’d always present whatever he had made with the self-deprecating: “no warranties expressed or implied.” Dad was a humble man.

Yet, he had so many friends and admirers. I didn’t even know how many until the day of his funeral.

We held his funeral in a small country church, because we knew that he would have liked that. I was surprised, twenty minutes before the funeral was set to start, when the mortuary helpers came scrabbling around the basement (where the family was gathered), looking for folding chairs. “It’s standing-room-only up there,” they said. “We need more chairs.” The little church was packed, and after the funeral, the caravan to the cemetery was over a mile long.

Dad would never have believed that that many people would come to his funeral. I can’t wait to tell him someday.

Dad loved babies, and always quoted his mother who said Christmas was best when there was a new baby in the house.

I could go on forever…

…But I won’t. This post is mainly for me, anyway, and if you’ve read this far, well, God bless you.

I hope your dad is a good one, too, and if he is still living, give him an extra hug as soon, and as often, as you can. Tell him you love him–often. Time flies.

xoxo

Amy

Here’s Dad, full into story-telling mode.

Thanks for popping in, gentle reader.

xo

Amy

Oh, Amy. I am so very sorry for your loss and the heartache you now have. You will miss your father immensely until the day finally arrives when you will see him again, every day of Forever. Here is the gift of a favorite beautiful old quote that I came across many years ago:

“I can still believe that a day comes for all of us, however far off it may be, when we shall understand; when these tragedies, that now blacken and darken the very air of heaven for us, will sink into their places in a scheme so august, so magnificent, so joyful, that we shall laugh for wonder and delight.”

–Arthur Christopher Bacon

You are in my prayers, friend.

Kristine, That is beautiful, and a balm for my heart. Thank you. *hugs*

While I only knew your dad through you & your stories, I do have one of his rolling pins and I love it. It is one of my favorite kitchen items. **hugs**

This was so beautiful to read. I learned several things about him I didn’t know. He was such an amazing man.

He was amazing, wasn’t he?

Deepest Sympathy.

Thank you.

Sorry for your loss. He reads like a good man, and a good father. I love stories about kind people living a simple, decent life. They make me hopeful.

It’s been 2.5 years since I’ve become a father, and I’d love my daughter to write about me the way you wrote about yours. I’ll start by learning why birds fly in a “V”. Wish me good luck.

Congratulations to you, and good luck! I can tell you one thing that Dad excelled at: he would do anything to help his kids, when we were young, of course, but also after we’d grown up. It wasn’t until the last two years of his life (when he was dealing with some challenging physical issues) that he would think twice before jumping in to help us with problems or projects. Until the, when we asked for help (and sometimes when we didn’t!) his answer was always YES.