It’s a mystery: which of your hens are laying eggs? Here’s how to tell!

Updated in September 2017, gentle reader, just for you:

I have two important tasks that I need to accomplish today:

- I need to make some peach pies, and–

- I need to figure out which of my old hens are going to live, and which are going to die. 🙁

I’m looking forward to the pie-making. Not so much the hen-culling decision.

It’s an anxious week or two that I spend every year about this time. A good share of my faithful old laying hens are heading for the freezer, and a few will be privileged to live another year *sigh*.

If I had my ‘druthers, and if money grew on trees . . . I’d have a chicken house with much different dimensions from the one that I have: it would be vast, with a high ceiling and several rooms. Big windows would let in lots of light, and mice would not be allowed inside, under no circumstances!

In this dream chicken mansion, there would be many rooms: one room would serve as the nursery whenever there were baby chicks, or mamas with babies, and the main room would be fitted with so many nesting boxes that no hen would even consider laying eggs on the floor or under the perches. Also, there would be a nice tidy room big enough for a goodly supply of hay, straw, and plenty of feed.

These hens are warming themselves under a light bulb that I keep burning on the coldest days.

As long as I’m dreaming . . . there would be a hydrant inside the coop, and a big sliding barn door that would make the periodic cleaning out of the used bedding as effortless as it possibly can be. Every few months, a kindly farmer (with a sparkle when he smiles–*ding*!) would drive out and give me a gift of several months’ worth of feed, just because he’s nice and he likes me (hey–I could make him pies–peach pies!), and I’d keep just as many chickens as I like, regardless of whether they were producing eggs or not.

That’s the dream. The reality is this . . . we built our own little coop many years ago, when we first moved out onto our acreage, when my dreams (and my savings account!) were much, much smaller. All I hoped for at that time (having just moved to the country from town, where chickens weren’t allowed at all) was a coop big enough for a few hens.

That’s it. Incidentally, that’s all we could afford to build at the time, anyway, so my good husband and stalwart sons built for me a nice little concrete-floored coop with one main room, and a teensy room for garden tools. Bryan built it sturdy and well-insulated, with windows and a screen door. I’m thankful for it, still, though it is very small, and very difficult to clean out, due to the complicated (I won’t go into it now) door situation. But anyway. I’m grateful.

Here is my daughter Amalia, Lucy (our goose) and little Mack, in front of my humble chicken coop.

As it is, the “tool room” quickly became the “nursery” where I could sequester new chicks or a broody hen wanting to sit on eggs, or even an ill or injured hen, when the need arose. (If you’re planning to build a chicken coop, keep in mind that you’re going to need two rooms at times. Trust me on this.)

Since Year One, I’ve had too many hens for that space. Always. I try not to read the “suggested space requirements per hen” always mentioned in chicken books, because it only serves to make me feel guilty.

I keep a lot of chickens in this small space, and a very sweet old goose. Several ducks, usually, as well. Many of the hens are older (two or three or even four years old) and then there are this year’s pullets, and a few roosters. At least they spill out of there the first thing in the morning and don’t go back in until the last thing in the evening, with an occasional foray inside to lay an egg, or take a nap.

My chooks are like me: they’d usually just rahther be outside, thank you very much.

That lengthy, possibly-unnecessary and probably-tedious introduction is to explain the problem of the old hens. I’ve made a date in a few days to take my Cornish Cross chickens (which are outside in a temporary shelter, as pictured in this post) and probably about twenty of my old hens to the butcher.

Butchering the old hens–which range in ages from two to four or even five years old–is what causes me no little bit of anxiety and guilt each year, but it’s got to be done. I’m getting 8 or 9 eggs every day from those 30 hens, which (as you might guess) is not a great ratio. It could be worse, and it would be, if I let these old hens get any older.

Which to keep—-which to keep??

Once this year’s batch of pullets begins to lay eggs (in about a month) I’ll get approximately 25 or more eggs a day from those 30 pullets. I like that ratio much better. A typical hen lays an egg nearly every day for the first year, and then the number of eggs she lays go markedly downward.

So this is the tough part to figure out: which old hens are still laying eggs, and which are not? Some hens naturally are not as ambitious and will stop laying early, and some will continue to be productive layers through their second or even their third year. I loathe the idea of butchering a good layer, and I don’t have enough space or cash to keep the hens who have given up laying for good.

Feed is expensive stuff these days, as you know, Gentle Reader.

So I’ve studied up on this matter through the years, and I’ve come to this conclusion: if you really want to tell if your old hen is laying or not, her bottom will tell the tale. Now the following information (not to mention the photos!) are not for the squeamish, but I’m figuring that if you’ve read this far that you’re really interested in the subject matter, ergo, my mentioning the parts of a chicken’s bottom will not shock you. Are you ready to proceed? Yes? Okay, here goes.

First, there are things to look for when you cull your non-productive hens, and I’ll list those things here, before we get to the bottom of the issue.

😉

- Feathers. The feathers of a productive laying hen generally are dirty, worn, and raggedy looking, since this hen is concentrating her energy on producing eggs and not on preening and replacing her dirty feathers. She is not spending much time in front of the mirror, per se.

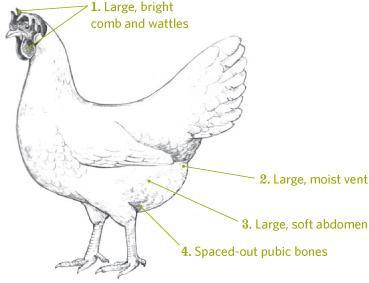

- Combs and wattles. A non-producing hen will have a scaly, pale, and shriveled comb and wattle, while a good layer will have waxy, full, bright red ones.

- Carriage. A good layer will be alert to her surroundings and not be listless and lazy. Her eyes will be bright and she should be relatively active (such as scratching in the litter, running around with her companions, etc.).

- Skin. Depending on when you check, and what breed of chicken you are looking at, a hen’s skin should be bleached, while non-layers will have darker-pigmented skin.

Those four signs are good indicators, but you’ll find that each one has its exceptions and oftentimes is vague or non-conclusive.

That’s why I insist that the bottom of the hen tells no lies.

The bottom of a hen that is in production (in other words, she’s laying eggs) is quite different from the bottom of a hen who has decided to retire from egg production, or who is going through a molt.

I spent a cozy hour in the chicken yard with my daughter Amalia, showing her how to tell which hens were laying and which were not.

The drawing of the hen at the right shows a typical productive hen: she has a good looking comb and wattle, her vent (where the egg comes out, and also her droppings) is large and moist; her abdomen is large and soft, and the pubic bones are wide apart.

Now for comparison’s sake, I started with one of my young pullets, because I knew for a fact that this young chicken hadn’t laid a single egg yet.

We’ll call her Pullet #1:

You will notice, along with the usual rather startled and vacant expression on this pullet’s face, that her beak and the skin around her eye has lots of yellow coloration. Once she begins to lay eggs, it will quickly fade to white.

Her feet are also quite glossy, thick-skinned and yellow. This yellow coloration will quickly begin to fade when she begins to lay, and then will be replaced when she stops laying. Pretty cool, eh?

I ruffle her soft bottom fluff and find the vent, with some difficulty, I might add. It is very small (about the size of a dime), hidden, tight, and dry. She has never laid an egg, it’s pretty obvious.

Now I locate the pubic bones, on either side of the vent. They are so close together that I have my index finger on one pubic bone, and my third finger on the other. Bless her heart. Amalia murmurs sympathetically with the pullet, and apologizes to her that this picture will be on the World Wide Web within a few days. We let the pullet go.

We proceed to Hen #2:

She is a different breed, of course, but the basic principles apply to all breeds. You can see that the tip of her beak is faded and white. I suspect right away that she is a productive layer.

The bottom of her feet also indicate a productive hen: they are faded and a pale white.

You can’t tell it very well from this photo (sweet Amalia, who took these photos, is squeamish about the bottoms of chickens) but this hen’s vent was large (nearly the size of a silver dollar) and moist.

I can get three of my fingers between the pubic bones! I’ve found a productive laying hen! Hooray! She also has a sweet, docile nature, and I’ll tag her to live another year. We bond.

To confirm my suspicions, I find that four of my fingers easily fit between the vent and the keel. She has a broad, large, soft bottom. (No human parallel here: is not my self-control admirable today?)

Okay, we’ll go to one more hen, and I’ll let you be the judge this time, Gentle Reader. She is the same breed as Hen #2, so they should be quite similar in build and coloration. This is a friendly quiz, and you’ll find the answer at the bottom of this post.

So this is Hen #3:

First, we’ll look at the color of the feet. What do you think? Are they as bleached as the feet of the productive Hen #2? Or not? (Check the photo above.)

Here’s her vent, which is smaller than a quarter, and is dry, and tight–not as tight as the pullet’s, however. What do you say, Gentle Reader? Is she in production, or not?

My fingers are resting on the pubic bones. See how close together they are? I think you’ve probably come to the same conclusion that I have, but there’s one more test:

I can fit only two fingers between the vent and the keel. What do you think?

Okay, I’ll tell you. I chose this hen for comparisons’ sake because I knew for a fact that she hasn’t been laying all summer long. She has been broody and has been trying to sit on eggs for months. Once a hen goes broody (bless her, I know the feeling, I do) she loses interest in laying eggs and goes into a trance of sorts, sitting on anything or nothing, for weeks. So if you guessed that Hen #3 is not productive, then you’re a pretty sharp cookie, Gentle Reader, and you’ve been paying attention, also.

(By the way, I didn’t send this hen to the butcher. She was just two years old, and so I encouraged her to go outside every day, by removing her from her nest and sending her out at breakfast time, and within a few weeks she was no longer broody, and was laying again.)

Now after all that, one more bit of advice: take your time on this decision.

Watch when you go in to the coop to pick up eggs. Which hens are busy in the laying boxes and which are not? If you take the time to observe the behavior of your chooks, you’ll figure this one out. You’ve got this one, Gentle Reader. And so, when you’ve made your final decision and you’re getting ready to butcher your old hens (or take them to the butcher shop) you’ll have no regrets.

(By the way, at our house, if a hen gains the popularity where she is named, she stays on our place forever, never mind if she is laying or not. So beware the naming of hens!) 😉

Also, one more thing: if you don’t keep lights burning in your coop during the winter time (read more about this in this post) to urge your chooks not to go into molt, you might mis-identify a younger hen who has just gone into molt and is thus taking a break from laying for a month or two. Yup. That’s a tricky one.

Molting, and whether or not to allow a hen to go into molt, and how to tell if she is in molt, is another issue entirely, and is pretty controversial in the chicken world. I try very hard not to let my hens go into a molt, but this is a personal decision.

Here’s my simple secret: for my laying hen flock, I vary which breeds I buy every year. For example: last year I bought Rhode Island Reds and Barred Rocks for my fresh laying flock. The year before, I bought Buff Orpingtons and Araucaunas. Since all these breeds are easy to identify from each other, I know which ladies are older, so the younger ones I’ll give a pass, even if their bottoms might indicate that they’re not particularly productive.

It’s not as complicated as all this might sound. If you have any questions, please do make a comment below. I try very hard to answer all questions.

Now! I’ve got to get busy examining all of my hens, since the sun is sinking and they are all half-asleep on their perches at the moment, or should be. It’s much easier when they aren’t darting away from me with shrieks of alarm. It may be a trick to get Amalia to help me again, though . . .

Of course since I made the peach pies, I’ll have a bribe to offer my daught, and maybe I’ll have more than one helper . . . ah, the persuasive power of a fresh peach pie!

By the way . . . usually when I’m doing tasks like this one, these are the gloves that I use. I love them. They are thick enough to protect the hands, but they feel like a second skin. Honestly. I’m not a glove person, but I wear these all the time during garden season!

Thanks for reading, and for commenting, and for sharing. Perhaps you’d like to join the fun over on my Facebook page or put your email address in the box to the right, above, to get more helpful posts like this one in your email box right away when I post them?

And if I could ask you a special favor, if this post was helpful at all to you . . . would you please share it with your other chicken-loving friends? Because who knows–they may be in a puzzlement about this issue, too! 🙂

And, hey, guess what? I’ve written an ebook that reveals over a hundred of my best chicken-raising tips and tricks, borne from raising and nurturing my homestead flock for over a decade and a half. Snatch it up here for a song!

Thank you so much!

*hugs*

Sounds like you’re having quite the adventure. Hope you can get through your day quickly!

Susan Dusterhoft

Today’s Working Woman

todaysworkingwoman25.blogspot.com

Great tutorial!! I need to identify my non layers asap before they drain my dry, and this is the best guide I’ve ever even heard of. Going to share with my chicken friends.

Good luck, Beth!

I’ve never had hens or any animals really, except the odd pet. I’ve not even started to grow my own vegetables yet! Good luck at finding the eggs that are and aren’t laying eggs.

Thanks Alexandria!

I’m sorry, that should have said hens that aren’t laying eggs, not eggs! My fingers were typing way too fast for my brain to think about it.

My mom use to do this on a yearly basis too. I hated this time of year because of the butchering. I wish I could say it was in defense of the poor dear chicken but it was because of the smell of wet feathers and picking them off the chicken. But I did enjoy the eating of them. Good luck on your culling.

Shawn,

We’ve butchered our own hens exactly twice, and that was enough of that for me! I found a small place that will butcher my hens for me for just a couple dollars each, and I consider it a worthy investment not to have to do the dirty work myself.

Goodness, I love learning new things every day, I can now pass the ‘Chicken bottom quiz’ with flying colours. Now, what to cook??

Anita-Clare, dear friend, maybe roasted chicken might be good for supper?

Amy, You never disappoint. I have never lived on a farm or for that matter been around chickens but you bring them to life. Your knowledge & compassion for these creatures is noted. I cannot imagine what it is like for you during this time of year, but your wisdom puts food in the freezer, thus the cycle of life.

Without having to scroll up, I was able to determine (according to your information) that the last hen you showed was no longer a layer by the dry rough feet. It is sad that they recognize they are no longer laying and want to roust on other’s eggs.

Thank you for this lesson. I always enjoy your contributions even if I am a suburbanite. I am hankering for a small greenhouse though.

Susie,

You are a very kind friend indeed to read the post all the way to the end, though you don’t have chickens of your own!! Although you never know when this knowledge might come in handy . . . 😉

I need help in figuring who of my flock is eating the eggs? Do I need to sit in the coop all day to find out?

Pam, that, or install a trailcam? I’ve actually caught the egg-eaters in my coop IN THE ACT, with yolk dripping from their beaks! Not cool!! It does help to pick up the eggs several times during the day, to break the egg-eaters of their habits, by the way. If you have time to sit in the coop all day 😉 maybe you could just run out there several times a day and grab the eggs up before the egg-eater has time to settle down and have a snack!!

I have also heard that as you are collecting them more often, replace them with the fake ceramic or wooden eggs so that when the egg-eating chook attempts their deed, they don’t get anything out of it. After doing this for a week, they don’t see the benefit and cease their evil deed. I have never tried this because so far (only 4 months) I have not had this issue with my hens.

Regarding this examination time, is it best to do during the spring/summer months? Or does it really matter what time of year?

Dawn, I would do it during summer, when egg production is likely at its highest. You may have some hens molting during fall and winter.

I have had chickens for a dozen or so years now and have never had a hen or rooster eat an egg that was not broken or cracked. I have even fed older eggs back to my flocks to make room in the frig for fresher ones and when I throw them out, if an egg escapes my toss, the whole unbroken eggs will still be there for days until I go crack it open. IMHO, when an egg is accidently cracked, it is natural for a hen to clean up the mess the best she can.

Since I try to live in harmony with nature, I do not supply artificial light in the winter, to force more egg production. Instead, I seal the eggs gathered in late summer and into fall, so they stay good all winter, when the hens are producing less eggs. An egg shell looks solid to the naked eye, but is porous to allow air to penetrate into the shell, as the little embryo grows inside the shell into a little chick. Air is also what makes an egg go bad after several weeks in the frig, but if you seal the shells, with a food grade oil, that does not go rancid easily, like plain old mineral oil, you can keep them for several months during the winter. After 4 months, don’t expect a nice high yoke, but they are still great for 6 months for scrambled eggs, cooking and baking. If you are getting broken eggs, maybe your big fat hen may need a little more hay to hold her weight or additional nests so too many hens don’t try to lay in the same nest at the same time, although a broody hen will encourage her sisters to give her more eggs to set and I have seen a broody hen steal eggs from other nests, because she would like to have 30 baby chicks following her around than just 10. This is true with ducks, turkeys, geese, pheasants and all the other poultry I have raised over the years. Of course everyone has their own way of doing things and should do what suits them better, that’s just the way I do it and instead of buying more bitties from a hatchery, at a pretty penny, I hatch out my own every year for free. Since my girls give me more eggs than I can use and I grow all the fresh veggies they need all summer and fall, I use the money from selling the extra chicks and point of lay pullets to pay for any needed feed during the winter. I can grow soybeans for higher protein, but we eat a lot of sweet corn and always use up what is in the freezer from the year before, when the new crop of corn is ready to start picking in May – July. You can’t grow both in a 50’x36’garden, without them cross pollinating and then neither will be good, so like everybody else on the farm, the hens have to pull their own weight and pay for their own winter feed.

Celie, I really enjoy reading your tips! It sounds like you have a lot of experience and wisdom in the hen yard. Thanks so much for sharing with me!!

This was a great lesson! Thanks! When hubby and I move up to our future homestead and get chickens, this knowledge will come in handy!

I’m so glad you learned something new, Vickie! Good luck with your future homestead experience!

What a thorough discussion on how to assess your laying hens. I always hated the part where I had to dispose of some of my clucking friends. We ‘chickened out’. I took my nice hens to a local farm and brought others home from their freezer in one hit. They weren’t my birds, so I felt a little bit better.

Francene, that, my dear is a BRILLIANT move! You don’t have to eat your pet hens that way. We have a “permanent flock” of named chickens which we’ll never eat . . . “Little Red” and “Babes” and “Phillippa” and “Nelly” and “Butterscotch” . . . .

I won’t ever kill my girls–they will retire–We name them and pet them and love on them–good thing we only have 4

CM,

I totally get where you are coming from! It is hard to make that decision, but for me I like having a reliable source of good fresh eggs, laid by hens that are cared for in a humane way, so it’s worth the sacrifice to butcher the old girls when they are no longer laying.

Wonderful post! Thank you so much for the information! Sharing this everywhere I can 🙂

Thank you Bee Girl, I do appreciate the shares!

Oh dear. My last chicken owning was over 25 years so I have no production hens to practice on. And I have a true confession”: I didn’t always get rid of my non productive hens. And another true confession – after one time, we had a local processing plant (which did chickens but not waterfowl) process the chickens. It was so much easier that way. As for the “telltale signs” I knew about the beak and the legs. I chickened out on the “bottoms up” test. Thank you; this post actually brought back a couple of memories which allowed me to fly…er, sprint to the finish line of CampNaNoWriMo this evening.

Alana, I think we butchered our own chickens only TWICE and then I found a small processor who would butcher them for me, for less than $2.00 each, and so that’s what I do, gladly!!

We are brand new to raising chickens and we’re not even sure which ones are roosters and which ones are hens. We have Ideal 236 and Black Minorcas. They won’t be old enough to start laying for a couple more weeks so hopefully we’ll be able to figure it out then. We know from the cock-a-doodle-doo that we have one rooster, but the sad croaking of one we *thought* was a hen due to the difference in tail feathers & body may indicate she’s really a he as well! Time will tell. Thank you so much for sharing! (visiting from the Homestead Barn Hop)

~Taylor-Made Ranch~

Wolfe City, Texas

Enjoy your new chickens!

So, tell me, Amy, if a hen goes broody, does that mean she’s depressed? Is it a kind of menopause for hens? I hope it is so I will feel better about her end of days. I am impressed with your expertise on hens. I don’t think I could stomach that part of farm life, though. I would become broody myself. But I could definitely stomach those peach pies!

Suerae . . . she’s not depressed when she’s broody, although all her body processes slow down and she goes into a bit of a trance. Hens who are successful at raising chicks from eggs are not disturbed from this “trance” no matter what happens. Even if somebody removes the eggs out from under them! It’s really amazing. It’s a bit of a science, figuring out which hens will sit the entire 21 days to incubate the eggs properly. Probably they couldn’t even be distracted by peach pie.

Thanks for this very informative blog – I do not have chicken as of yet but am trying to learn as much as I can about them. This was wonderful and in terms that I could understand.

CJ, I’m so glad it was helpful!

This was extremely informative and the pictures made it “Who is laying for dummies’ – aka… me! I have leghorns as pets and don’t plan to remove the non-layers – at 65, they may out live me! My grandkids and friends join in our enjoyment.

Thank you and your photographer daughter — for the excellent presentation! How about a peach pie recipe???

Hmm . . . a peach pie recipe!? Now that’s a grand idea (snarfing down pie) let’s see if I can put the pie fork down long enough to jot one down, Cathy . . .

I’m so glad we didn’t have to check the Cornish Cross. Ugh!

I’m with you, dearie. 😉

very useful information !!! my chicken situation sounds a lot like yours … and your dream sounds just perfect to me 🙂 we are planning a bigger, nicer chicken coop for the winter and some of our hens will have to go before that too. I don’t know how to make that decission yet :S

THANK YOU for this information! I just bought some 1.5 year old hens and figured I’d keep them until the chicks grew up but I’m only getting between 1-3 eggs out of 5 birds and I’m trying to figure out who is laying. Wasn’t sure how to go about it.

Good luck–hope you find clear answers!! 😉

Awesome post!!! Thanks so much I really need to go through our flock and do this. But I do have a chicken question??? We have some Seramas separated off from the pasturing flock (my daughters show birds) that are with a Serama rooster. They began setting on 2 nests and never hatched anything so we removed the eggs. Will they start laying again?? They aren’t very old I would hate to loose the possibility of not hatching anymore of their chicks.

Thanks for your time and all the great info Dayna

Dayna,

I always love it when I find a hen who will go broody. So many of the newer hybrids have had the broodiness bred right out of them. I have a few bantam hens who do go broody every year, and I rely on them to raise chicks for me in the fall. I don’t really expect them to lay eggs, but they will lay eggs again once they get the broodiness out of their systems. If your two Seramas are still broody, you may want to go ahead and slip eggs that you suspect are fertile under them (they don’t have to be their own eggs) and let them try to raise their own chicks. If you’re only interested in the Seramas breed of chicks, then you could try taking them off their nests every morning and sending them outside to eat and drink and exercise, and they’ll probably get the broodiness out of their systems after a few days. Sometimes it takes a bit to break that cycle. But they probably will start laying again, if they aren’t very old, and if they’re healthy. Good luck with this, and let me know what happens!

All the best to you!

We are starting new again this year. I will have to start checking next year.

Thank you for your very helpful post! I found you from the Barn Hop last month and made a mental note to revisit here when the time came. We’re butchering chickens tomorrow, including 6 newly-determined non-layers.

Jill,

Good luck with the butchering! That is not my favorite way to spend a day, but sometimes it has got to be done!

You took the words right out of my mouth: “I really hate the idea of butchering a good layer, and I also loathe the idea of not butchering a hen who has decided to give up laying for good. Feed is expensive stuff these days.” This is exactly what we have been going through. We have been at it for three years now and still have some of our first girls! We realized our mistake too late this past year and now know we should be replacing them on a regular basis. Today we have 17 girls and got one egg….some days three or maybe four but it keeps going down. It’s time! I had a million excuses….it’s the changing weather, they are moulting, they don’t like the chain saw running and so on. So we are going to keep the few that are still laying and butcher the rest. I was elected to do the checking! That’s ok with me! Don’t want the other job. Hubby and son will do that as son will be butchering his meat chickens this week (at his house) thank you! Thanks for the information….by what you taught, I think I already know what ones we will be keeping.

Peggy, I know it’s a difficult decision, especially if you get attached to your hens. (I do!) Here’s what we do: we buy a new batch of chicks every spring, and butcher the old girls that are no longer laying (usually 2 or 3 year olds) and put them in the freezer. They make incredibly good broth, and that does salve my conscience a bit! And we always have lots of eggs!

I’m a little upset with you for culling your hen just because she’s broody! Have you attempted to get her out of the broody trance? We have a hen that gets broody but I can get her out of it by removing her from the nest and if all else fails cooling her off in a bucket of water. Much better then culling her! Don’t get me wrong I understand culling unproductive hens but not if you haven’t tried to solve the broodiness.

Maria,

Oh, I didn’t cull her just because she was broody. I try to keep just enough hens to not over-fill my coop (it’s not big) and 30 is about the top number. She was an old hen to begin with, and constantly broody, yet failed to hatch out eggs when I moved her to a “private” area. I’m not so heartless as to cull a hen just because she goes broody. In fact, I especially appreciate hens who will go broody and then actually follow through and raise baby chicks. I’ve just never had very many who have been successful to that end. Usually they’ll sit for a week or two, then abandon the nest, and I believe this was the case with this particular hen. Non-productive, old, and not a good sitter, either. I have several bantams who get a free ride no matter how old they are, because they’ll hatch out a batch of chicks now and then, and because we’re all attached to them.

Thank you for this informative article. I have to do this SOON but am so scared to find a bunch of eggs inside if you know what I mean! Could you come over to help? :o) Koddos to your photographer.

Good luck! I never like trying to decide who lives for another year, and who goes in the soup pot, if you know what I mean!

What would a hen’s bottom look like when she is molting? I have an older batch of hens that aren’t laying at all (there is one with a nest elsewhere, however). If they are only molting but still capable of laying again after the molt, they would still exhibit the signs of a laying hen (I think). Are what you saying is that if their pubic bones are close, abdomen tight and small, etc, that you can be sure they’re done laying for life vs just slowing down due to molting.? Just wanting to be sure I don’t mis-diagnose and get rid of a hen that’s only slowed down vs one that is totally done for good!

Thank you for your very informative post.

Kathy,

If your hen is molting, I’d wait on the egg-laying diagnosis. Since she’s not laying, it’s going to be difficult to tell because from my experience molting hens are another animal entirely. Instead, I’d go with her age: is she 3 or 4 years old? Then chances are, she’s not going to lay many more eggs. If she’s just a young one (1 or 2 years) I’d let her get through the molt and see if she starts laying again, before making a (cough) permanent decision that you can’t undo, like chopping her head off. When I buy my new pullets in the spring, I always choose different breeds from the year before, so I know by color which hens are new pullets. For example, this year I bought Rhode Island Reds and Barred Rocks, which look completely different from last year’s Red Sex Links and Silver Lace Wyandottes. Of course I always buy a handful of Americaunas, because I dote on the blue eggs. 🙂

I had to chuckle when you said molters are a different animal altogether. I tried “diagnosing” them on Saturday with my daughter. I told her all the ‘symptoms’ we were going to look for, and after about 2 hens, we realized that they were not exhibiting the (ahem) proper symptoms. I guess I should say ‘presentation’ instead of ‘symptoms’. Some had soft tummies, but small, dry vents, or not much room between the bones, but plenty of space between keel and vent. Too confusing! We gave up and went to seek a hen that we knew was laying to see what a ‘working’ hen’s bottom really looked like. She, however, was ensconced on her nest and doing her best to look invisible, so we decided not to bother her.

We do the different breeds for different years, too. Makes it so much easier. Yes, these were Spring 2010 models so they’re probably ready to go to the next phase of a hen’s life after egg laying. Thanks for your advice. 🙂

Good luck with it, Kathy! Sometimes the old girls just need to go . . . although if they earn names at our place they will stay forever . . . like “Little Red” and “Babes” and “Colorful” and . . . and . . .

I was just talking with my husband about this today. I didn’t know how to figure out my layers from the just eaters so I was going to borrow his game camera to see who is going in the nest and who is not. LOL Think I might try your method instead. Thanks for the info!!

Sarah! Wow, that’d be a great experiment: set up the game camera and tape your hens for a couple of days, and then ALSO do the evaluation that I write about. See if they match up!! Let me know the results and I’d publish a Part II!

I have been looking for this info for a long long time. Thanks so much for going through the trouble to write this. I have wasted so much $ on food.

got to do this right away.

Yep, Dana, good luck!

I am glad that I found this information – you are awesome – however that just means that my assumptions are correct and I have two that will end up being dinner instead of providing me breakfast. I am waiting a week and watching all of them to ensure that I am indeed correct with your information before culling. Thank you so very much. This was just the information I was looking for!

Yes, Denise, do be sure to use a wait-and-see period, if possible, to see if your old hens aren’t laying. I hate to butcher a hen who is still laying. I usually wait so long that there’s absolutely no question . . .

My wife and i laughed till we cried because it was describing me. After 3 years and 40 plus chickens, my lovely and indulgent co-conspirator in life informed me that something had to go. Meaning me or some chickens. Being a big strong male, i knew i could butcher them( i had no intention of leaving). Two hours after starting she found me with one dead chicken and eyes swollen shut from crying. Thank the lord for amish neighbors. I give them one for every 5 they dress out. No one though will ever touch my bantams. Your blog is a treat.

Oh Mark, I really needed to read this comment today! Thank you! JUST YESTERDAY I had to take some old hens (and some ornery old roosters) to the butcher, and I dreaded it for DAYS. I’m so relieved that that ordeal is over! Today’s blog post is just for you. (Nobody will ever touch my bantams, either, even if they–and I–live to be 100. And I have quite a few of them.

Dear Amy, my lovely wife and I found your blog while researching the lack of eggs from my girls. (I need to clarify something at this point. I’m a city boy, she’s a country girl.) She knew what was wrong with the girls, I didn’t. She makes me research this so I will know what’s going on with them. That’s how I found your site. I never ever respond to a blog till I found yours. She wanted me to tell you what compelled me to comment. Quite simply it was your amazing hands. My grandfather always said that eyes are the windows to the soul and hands will tell you almost everythingyou nneed to know about a person. What a blessed and lucky family you have. Yours most sincerely, Mark, from Ethridge, TN.

Oh, Mark, my hands? I used to be proud of my hands, but now . . . well. They aren’t as young as they used to be, you know? Thank you so much for making my day–two days in a row! I hope you saw my “Vacay” post yesterday! Do keep me posted on your chicken adventures!

I am having trouble determining…I have quite a few that will have large generally moist vents, but they will either have only 2 fingers between the pubic bones OR barely 3 between the keel and pubic. There doesn’t seem to be any age connection either. Some of them are old (4-5yrs) and some are (1-3yrs). There are about 25 and I’m only getting 6-8 eggs a day. Would it make sense that many are still laying, but only 1-2 x’s a week in an alternating pattern? Or the younger ones are molting? I didn’t find any that had dry or small vents…ackk, what if I butcher layers or just taking a break…

Tara,

The thing is, it’s an inexact science, to put it mildly. Probably what you have is a whole bunch of hens who are laying a couple of eggs a week. To simplify the process, I usually buy a different breed (or two) or hens each year. That way I know how old each hen is. This year, my youngest hens are RI Reds and Barred Rocks. So it was an easy decision to butcher the Buff Orpingtons (though it still made me sad) because I knew they were 3 or 4 years old. In general, if a hen gets looking very fat and comfortable and sleek, she’s not laying. If she looks lean and a bit scraggly, she’s a working girl. If I were you . . . I’d probably just butcher ALL the 4-5 year-old hens (except for special named pets, natch) and keep the 1-3 year old ones. Chances are, they are laying at a higher rate. If you butcher layers who are just laying 1 to 2 eggs a week, there’s no particular loss, and you can always buy new pullets this fall and raise them for the spring. New hens usually lay an egg every day!

Yes, the older girls really have gotten fat. We are trying to hatch our own replacements and will need to band to tell the older from the younger next time, but different breeds per year is a great idea. Thank you.

Thank you for the info. I have raised all my girls from chicks and have had a few roosters and 2 turkeys. In all I have 15 hens and now 1 rooster and 1 female turkey who lays 1 egg a day bless her heart. I get 6 to 10 eggs a day from my girls. Being raised on a farm the butchering doesn’t bother me to much. I forgot how to tell who was laying still and took in 3 older hens last year and wanted to be able to check to see if they are still producing or if they are going into the freezer soon. We had our male turkey for Thanksgiving and at 6 months old he weighed a whopping 46 pounds 😉 Our friends pick on me about my spoiled girls because we converted our 10 by 20 wooden shed into a chicken coop taking old dog kennels and making nests for them inside. The female turkey got stuck in one so I had to go get a large dog kennel for her so she’d have her own nest. We remove the doors on them so they have free movement in the shed during the winter and are safe from the cats in our neighborhood. During the summer they have the whole back yard to enjoy with fruit tree’s, veggies and lots of grass to enjoy. I have one red hen that is almost a year old that has decided to sit so I have marked a couple eggs for her and she gets to try to hatch them. I really enjoy my girls and they love to follow me and our 2 dogs around the yard… Thank you again for sharing your info. This is the breeds I have in my backyard coop. 2 rhode Island reds, 2 Australorp , 2 Plymouth Rock, 2 silver polish, 4 Easter Eggers , 3 that I adopted from another farmer but I have no idea what they are they look between a Australorp and a Rhode Island Red. 1 broad breasted turkey. 😉

Christine,

It sounds like you have a very happy and productive little flock, and pretty, to boot, with all those different breeds! And what a happy thing, to have a broody hen! Despite the fact that most of the modern breeds have been selectively bred to coax that urge to brood from them, I always have several hens who want to sit on eggs. I do right now, in fact, in the middle of winter! It’s always a sweet surprise when a hen steals away and succeeds at hatching eggs, and then proudly shows up in the chicken yard with them! Here’s the story of one that did this last summer: http://vomitingchicken.com/well-done-helen/

Thank you for that beautiful story it touched my heart. My girl is being very determined and I love the noise she makes when I check on her. I marked the eggs I let her keep because I gather eggs daily but she doesn’t move other than to move her eggs around after my visit daily. She feels safe from the others and they will at times lay an egg in front of her where she will steal and tuck under her. I do love my girls and they are used to me cuddling them when I go to care for them daily. I know we shouldn’t become attached with our edible pets but its hard when you have raised them from Tiny babies. I don’t name them but they know I’m speaking to them when I call them my girls. The local feed store thinks Im nuts Im sure because I buy feed ever 2 weeks I ask them if they have a large bag of treats for my girls… LOL I hope my Rhode Island girl is a successful mamma. Should know for sure in about another week. 😉 Ive heard a lot about the bird flu in the chickens, does anyone know what the signs, symptoms are of this? My girls are not sick but I want to make sure I watch for the signs.. I don’t allow others to bother my girls and keep them safe from other animals but as a mamma to these girls its my job to make sure each and everyone is healthy.

Thank you so much for this post. We just butchered all our hens last weekend for the first time. We had 6 hens and they were all close to three years old and not laying other than us getting a surprise egg or two once a week.

We were curious how to know which one was still giving us an egg occasionally and thought about putting a game camera in the coop to watch the nesting boxes, but your post was very helpful for us in the future. We will be getting new chicks in April and starting all over again.

We did not like the butchering process at all and I wasn’t sure I’d be able to handle it or help my husband but I did and I handled it better than I thought but neither of us enjoyed the task. The wet, smelly feathers are gross!

I kept a lot of the parts to make chicken stock and I canned 6 quarts of chicken and 18 pints of chicken stock. Also my first time pressure canning. What an ordeal this all was but well worth it.

Thank you again.

Tracy,

I am so impressed! You took on a lot, all at once. You know if you do it again and again, someday it’ll be all much easier for you. And all those jars of chicken and stock will be so nourishing and handy this winter! If I have a lot of chickens to butcher, I admit that I take the easy way out: I make an appointment at the locker and get them butchered while I sit and drink coffee . . . 😉 . . . and then I put them in freezer bags and sock them away in my freezer. But what you’ve done is really admirable!

I have to cull some ladies from my flock this week. Thanks for the refresher!

Good luck and blessings to you, Sheila!

Pingback: Flock of Chicken Terms: P-Z | Treats for Chickens

This was very helpful and very well written. I smiled more today. Thank you.

Well, Eric, you made me smile with your comment, so you’re welcome!

This was just the article and photos I needed to see!! Not sure we’ll butcher any of the chickens just yet, but would very much like to know which ones are earning their keep – especially with the egg shortage now! Thanks so much for the good info!!! And the smile your blog put on my face!! I’ve signed up for the emails, too!

It takes a bit of sleuthing, Joan, and I do like to give the hens every possible chance before I put them into the stew pot. I’d keep them all if a. my coop was larger and b. feed expense wasn’t an issue! Thanks for your kind words and for putting a smile on my face!

You are a fantastic writer! I usually don’t like reading such long articles on a screen, but you held my attention the entire way through. No small feat, as my wife can attest. I suspect I have a hen or two not laying and was looking for information and this article has really helped. Thank you!

You are welcome! And thanks for the compliments! *blushing like a girl*

What color is the beak of the old non laying hen, #3?

Oops. That’s a very good question, Suzanne!

And….? You must’ve gone outside to check

We generally put rings on our hens; different colours for each year. It makes it easier to select for culling. The old ones are packed off for the local wildlife park where they are slaughtered for dingoes and crocodiles lunches! Very charitable! I hate pulling feathers, and my grand daughter thinks the whole thing is GROSS!

Gillian, could you do me the favor of sending me photos of these rings? I’d love to learn more.

Thank you so much for the tutorial on culling chickens. I’ve been raising chicks for over 50 years, & still have trouble….yours is the first really good help I have had.

Have you seen Grandpas feeders? We got two of them this year, & are very happy……absolutely no wasted feed…which is amazing…first time ever. Really, not a crumble on the ground! Our babies (10 wks.) Copper Maran, have reached the second stage of getting used to the motion of their weight opening the feeder… In a week or so I will lower the lid so no mouse or bird can touch it…..thus no loss, or disease introduced by critters. It can even be out in the weather all the time ( it RAINS here in the Willamette Valley, Oregon :). It is built very well, (I read one reply in their blog who has had his out in the weather for 10 years…still in excellent condition !). We have also made nipple waterers..so we can go away for days without bothering to do anything but gather eggs & check.

Thank you for your fun & newsy blog! We love the Lord Jesus also,…..& find His grace so amazing throughout all these 70+ years, & especially now that my dearest hubby is helping me face terminal cancer…the first encounter like it in either of our families. My chooks are a great comfort & delight to us just now. May the Lord bless & give His joy in this interesting world! Shari the happygranny of 42.

Shari,

What a blessing to hear from you! Wow, you’ve been raising chicks for over 50 years: I just know that you have lots you could be teaching ME. And 42 grandchildren, you are blessed, indeed! I’m so so sorry that you are facing cancer. I hope and pray that you will be able to beat it off, dear one. I’ll be praying for you, and I’d love it if you checked it with me whenever you can. *hugs*

Also–put a drop of food coloring in the vent of a chicken you are not sure about-if she lays there will be a mark on the egg 😀

Great tip, thanks Lisa!

Excellent post, now to find the time to do it! thanks Don

Wonderful article. I’ve been raising chickens for 30+ years and honestly, I have never checked the undersides of the hens. I usually just cull the old hens each year. However, some years I’ve allowed the old girls to stay and it really wasn’t a good thing. I’m in need of culling chickens right now too. I have my pullets banded so it’ll be an easy job. And hurray! My pullets are laying like crazy!

Loved reading this article. I’ll be back!

Oh, Jody, I love it when the pullets start laying. Those dear little eggs!

This was amazing info thank you so much. It was also fun to read because of the personal touches. I also buy a different breed each year.

Thank you Laura Tiffany

Thanks Laura!

Pingback: IT MAY BE TIME TO CULL HENS, 2015 | Outdoors in the Sacramento Mountains

what a strange way of thinking- these animals give you eggs for as long as they can then you kill them.

It may be strange to you, Kelly, but the truth is if I didn’t butcher–and eat–the old hens who stop laying, I’d go broke feeding pet chickens (contrary to popular belief, chicken feed is not cheap) and I wouldn’t have eggs OR meat to feed myself or my family. It only seems strange when you are accustomed to buying meat in the grocery store and don’t give it much thought to where it comes from. My hens live several happy years on our place—I pamper and baby them like you wouldn’t believe. I treat them like beloved pets. But a healthy hen could easily live 8 to 10 years, but only lay eggs for 2 (or at best, 3) of those years. Once she stops laying, she becomes a pet. I can’t afford to feed dozens (or hundreds!) of pets. I don’t know anybody who would. It makes me sad to butcher them, honestly, it’s something I dread. But I know that it is a natural cycle that I am participating in, and I’m grateful for it. And I am relieved to not buy the chickens in the store, those that are raised in crowded, cruel conditions.

Wow thank you so much for all the pointers and fab photos! I live in New Zealand and am looking forward to checking our chooks tomorrow to see who is going to survive. Many thanks for your great tips 🙂

Lisa,

Where do you live in New Zealand? We are planning a trip there in about a month!

this is a great informative article. thank you for sharing. i have only 5 hens; 2 RIR that are 10 months old, and 3 Black Australorps one is 10 months and the other 2 are somewhere around 2 or 3 years old. i have one of the older hens that only lays once a week and it is usually a super huge egg that is double yolk or an egg inside of an egg. do you think that she might be at the end of her cycle? thank you for this article 🙂

It really sounds like it, actually, like she may be nearing the end of her egg-laying years. Egg-laying irregularities like that (or very tiny eggs, too) are often a mark of getting to the end of the eggs that she was born with.

Such a great post! We only have two hens at the moment (our little trial flock) and one has stopped laying. Should we sought a butcher for just one hen or would you do things yourself? Seems a waste of time for a butcher but more humane…

Julie, if you only have two hens, I would keep them both, regardless of whether one is laying or not. Chickens are social creatures, and the second hen (if you butcher the first one) will likely pine away in loneliness. I’d never keep less than two chickens, fyi. Plus—especially if she is a younger hen (younger than 3, say) she may just be taking a break, especially since it’s winter (is it winter where you are?).

you did very well at explaining the natural of the hen. Was so well down that I look forward to more of your informative topics in the future .

Thank you so much for your post with pics!

It really helps.

Alternating breeds…brilliant!

Absolutely, Cristi! I think the alternating breeds is the handiest shortcut to this!

Best chicken post ever!! Wish we had read this years ago! Now I feel armed to cull my hens and get more chicks knowing I won’t be wasting feed on non laying hens. I do enjoy them all and wish we could keep them, but organic, non-gmo, no-corn/soy is expensive! Plus we do enjoy bone broth and knowing we are eating a super nutritious chicken! Thank you, thank you, thank you!! Bless you!

Cynthia, so happy that it was helpful! I’m amazed at how few chicken people know these simple analytical measures.

In the past I have put different colored leg bands on my flock. When my sons were young they showed chickens at the 4 Happy Fair. . The different colors made it easy to determine which chickens were which sons chicken. (Saved a bunch of “That’s my chicken ” arguments, plus gave those special feathered friends a longer reprieve from the fatal guillotine. ) We could also tell at a glance what year they came to dwell in our humble (extremely humble ) chicken palace.

Lisa, would you share with me where you bought the leg bands? That’s a great idea for how to tell the difference between different chickens, especially of like breeds. This just proves my assertion that I learn just as much (if not more!) from my readers than they might learn from me! Thank you, Lisa!

Thank you for the time you took for this post! My pullets aren’t quite laying yet, but I’m going to bookmark this post for the future when I need to identify which hens are reaching the end of productivity! 🙂 Thank you!

Thanks Dani!

Thanks for your info it help me a lot my first time razing chickens. God bless. How often should I change the hay in the coop ?

Mai,

I can’t tell you that–it depends on how many chickens you keep, and what kind of bedding, etc. This is what I do–I keep a pitchfork inside the coop, and once a week (on Saturday morning, usually) I take 3 minutes to fluff the bedding, removing any wet spots that might happen (like from a spilled water bucket). When the bedding seems flat or if it starts to stink, I add more. I use the deep-bedding method. I just keep adding an armful of bedding whenever I feel like it. About twice a year, I clean out the entire coop, adding it to my compost pile (in the spring) and/or to my garden (in the late fall).

I found your article and photos extremely helpful and informative. Thank you for sharing……it is always great to read and learn what others have been through. Share the knowledge….which, indeed, you have done so well!

Absolutely, Trudy, I hope it was helpful for you!

Oh my goodness! You just validated my grandfather. He came from a farming family, but didn’t choose to follow that course for himself. He thought I was crazy when I got chickens. He told me about his responsibility of culling the chickens. He couldn’t quite remember how he did it, but knew he looked at their feet. I never could find any information online about checking their feet. He probably blocked the rest of the process. Thank you! He is in his 90’s now, and I can’t wait to bring back a memory for him!

Shannon, I would LOVE to know what your grandpa has to say about the process!

Thank you thank you!!!

I am going to check our girls out super soon. I wish I had read your post sooner….our girls dropped production and haven’t picked back up after time. Now I know what to look for. Thanks!!

Hi my hen has continually laid for two year (from the start) and hasn’t had a break! Now she has stopped laying do u think she will start again?

Liz,

Without having seen your hen personally, my guess is that since she laid so well for TWO YEARS, she’ll pick it up again after she has had a break. She is probably going into a molt, and once her feathers all grow back, she’ll more than likely start laying again. What breed is she?

Have u an email as I can’t seem to put a photo on here

Hi Amy, this was really helpful and informative but I have a question can we apply these points to other poultry birds like ducks, quail or pheasant?

Anand, I have no idea about quail or pheasants. You’d have to do further research on them. As for ducks, I’ve had ducks who lay eggs sporadically for years and years. In my experience, they don’t ever lay quite as regularly as chickens, but will lay for longer.

Thanks

Pingback: To Cull or Not to Cull? - Homesteading Today

We have 5 1 1/2 year old Rhode Island Reds.

One of the 5 is consistently not laying. Others are spuratic if they miss a day.

We think we know which one is NOT producing

How do we get her to start laying again?

They were all laying in the about 2 months ago.

Hey guys, it’s really really difficult to MAKE a hen lay. In fact, it can’t be done. To help your hens lay better–all of them–(gosh this is a post I need to write!)–I’d provide lots of green things for them to eat, fresh water every day, good deep litter in the coop and out, a supplement of egg shells and/or oyster shell made especially for hens. Your hen that is not laying could well be going into a molt, and if so, let her be. Once she grows her feathers back in, she’ll have another go. Good luck!

Good bit of reading here, many thanks.

I think that made my lightbulb light up was the idea that, in the same way that a gardener rotates her crops, the Jenn keeper can buy a different type of hen year by year!

I know you didn’t exactly do this but when you said you would buy a different type of flock every two years I thought that was a brilliant idea.

I currently live on my daughter and her husband’s land so I’ve not been given permission to keep hens – yet! But if I manage to persuade her, I’ll start with three Buffs, then the following year some red hens, then maybe three Black Rocks after that…. I’d know exactly how old which birds are.

I love this idea. Whether I’d be strong enough to cull them, I really don’t know…

Absolutely, Lynne! It’s the easiest thing of all, to just rotate breeds–if, in fact, you aren’t really attached to a certain breed! Of course some hens still will lay better than others–I still feel guilty for butchering a couple of 5-year-old hens this summer that were still laying! (Wish my coop was larger!!) And–no worries about the autocorrect. It’s something I struggle with, too.

Apologies for breaking my own rule and not reading through my post first.

Jenn keeper – damned auto correct? Hen keeper, of course.

Lightbulb sentence – poor writing. hmmm my fault too I fear.

I’ll put it down to sheer excitement.

I had three hens a couple of years ago but had to rehome them when I had to sell my home. Fortunately they live with a new chicken mummy who adores and spoils them. I still miss them though.

Very very educative, thanks very much Amy you’ve enlightened me and now i’ll know how to cegregate my layers. Decide whether to dispose them and replace with day old.

Very nice things to read here and often between trying to read as serious as I am , a laughter for the nice humor , really down-to-earth , just my style 😉 . I am at this moment some kind of shelterkeeper at home lol 🙂 . I found two hens , totally in a very critical condition , I can’t describe it other than it is obvious the poor chickens have been dumped due probably the fact they seem to be a little bit older plus the fact I noticed a coop where usually only old hens were is now filled up with pretty and very young aged chicks . But again , I said critical due the following ; first I used to have one , found her in some kind of towel bound with both legs broken on the public road in the side of a forest , more a bedding of an empty river , she was fully conscious but unable to walk away from me and the towel was at first in my idea like ” oh dear , what did you do , that happens if people leave their trash just on the side of the woods urghh so you got stuck , no worries I’ll set you free so you can go home ” with my stupid clueless enthousiastic smile on my face I said ‘ you silly how did you even do this haha ‘ but now the towel or whatever kind of filthy thing it was I notice the most pethetic sight ever , I got a bit shocked first and my mouth ? that just fell open ! The poor chicken has obviously some sever injuries that if left untreated can soon end up into a funeral . The horror ? both her legs not only broken but also EVERY SINGLE TOE ! so now I was more thinking about a hit and run but that road , it is a road of dirt which only on occasion gets used by cars so I began to check on her once I took her in my both arms because even her head had to be supported , both her eyes shut , blood everywhere with such a great mixture of dirt I couldn’t even know what kind of breed nor color she was , so once inside the conclusions after a first check up ? broken legs , wings , toes , bold areas on belly , back , neck , like it was done by some animal ( now knowing that I was right , the owner must be an animal ) so kept her warm inside the house but she couldn’t eat nor drink , used to work with a vet and even tough that was in another life I started to think about all her injuries and the possibilities I had to take care of her , strapped every broken area including the legs with bandage , tape and some straws for support , now one week and half later she can finallyyy stand on her own , the work began to waigh hard on me too since I was right in the middle of several projects of work yet took time of to handle it at home while caring for her . She now eats just fine , every day she starts to act more like a total healthy chicken , I’m so happy with her in fact , even while she doesn’t lay eggs , it is a nice hen and it looks as if it is a real fighter too ! everyday is a better day for her and so for me but then again , I have been swearing for this in fact , the same road at the side of the woods again another hen , this time without the towel , yet even worse both legs bound together with a WIRE ! I did the same things again like I did with the other hen and surprised I was after bathing her ? indeed the same breed / age and injuries ! this had to be done only few hours before I got here because she was still having a terribly fast breathing and she was looking with huge pupils in her eyes , the look of fear got even inside of myself ! She is so traumatised I can barely help the poor hen so I decided to just first let her become a little bit calm inside of her and kept her warm but now she falls like dead on the ground and has trouble breathing , only option left ? HOPING for her to survive yet almost given up due the behavior ( head just falls whatever side , beak open , eyes closed , weird twitching and shaking but because of the fact I never wanna die alone I decided to wrap her up in something warm and to take her in my arms while she ‘d let go so she would atleast had have , for the very last moment in life the feeling of being safe and warm with knowledge somebody loves her , as we all know they are very intellectual gifted in fact , as I sat outside in the sun with her in a blanket on my lap suddenly she starts to make sqeeking noises and opened up her eyes , I tought this was due the pain or so , no no this animal FELT that she has been given a chance 2 survive and live a good life , she just kept observing my face , especially making extreme good eyecontact !! this moment , yah thats me again I just started to cry like a baby without breastmilk but she noticed ‘me ‘ and just seemed to be so comfy that I throughout the tears couldn’t resist laughing , I said ” you are soooo damn screwed u know and it hurts me to know that people do this to animals like you but I will be there untill you are flying ok ? ” she started looking around in my small backyard and suddenly she even forgot about her injuries and jumped out the blanket into the grass ! she was ok ! ( the magic in my eyes is still not a proven scientific fact but it is magic anyway ) but ok she is alive and unfurtunately not able to eat , drink etc , very sad to see in fact and I do what i can , she maded progress tough , she can walk already but not that steady and not often , now suddenly they were communicating to eachother , both in another room 🙂 so I wanted to try something , the are both having same problems and they no doubt know eachother so I started to be as clumsy as usual and build a small pen for indoor ( my house is without a single doubt as dirty as yours ) to put them together and miracle miracle ! they BOTH recover better ! But here comes my question and very VERY bad news ! the two hens seem to have different ages BUT I have no clue so I can’t know anything about how many times they would lay eggs and the condition they both suffer ? yeah , you can guess :'( , they’re both eggbound :'( , one can’t lay her egg due the fact that also her tail and a part of the vent is so injured that it must hurt for her to pass an egg ( tail looked broken yet after two days she could put it up again so I guess not ) , I have been using all the veterinarians meds I used to have for my animals that are now sold to others yet nothing works , I lubricated them , I have been bathing them nope nothing and the clock is now ticking , the question ? can I help them by knowing their age since the dosage of calcium can’t be given constantly by a young hen that can cause her to die if she keeps producing , if it is an old one that would lay like your old ones ? i can higher up the dosage without the risk of another egg getting into the ovary , right ? how can I find out their age ?? kind regards and plse forgive me any grammar faults etc , it ain’t my own language 🙂 .

Vicky, I’m sorry that I didn’t see this comment until now. I’m curious: how is your hen now? It sounds like you are doing everything you can for her. I hope she has pulled through! I have been amazed at the resiliency of chickens!

Wonderful Information. We have a few chickens, 30 of various ages and will need to be having this stressful decision process in a short two years. we have been through the Cornish Cross debacle ( as a dyed in the wool carnivore, I had a hard time with this breed once they came to butcher age. hard to think of these really young but HUGE birds as mature enough for the freezer. We will not be getting this breed again,) Like you, we wanted a large chicken home, room for all, and easy to clean. My blog listed in the info for posting this reply will show one version of a chicken mansion that is human, chicken and cleaning friendly. It took us just a month to build and while I do believe free ranging is best for the chickens, I do not want my birds to be my neighbor’s dogs dinner. At 20′ x 30′ our wired and aviary netted pen is getting cramped as the little ones are growing so we are moving up to [4] 30′ x 30′ pens off a central ‘hub’ pen where the coop will be located. We plan on rotating the four new pens to keep the birds from scratching the grass into raw dirt. Thank you for the great advice.

I like your ideas, Ken, especially the rotating of the four pens. I’d love to do that myself, at our place. Although by using deep litter in my chicken yard, I have managed to grow plenty of vegetation in there for my flocks’ grazing pleasure. 🙂 This deep litter idea is not embraced by everybody, apparently, but I do like it a lot.

http://vomitingchicken.com/preparing-chicken-yard-winter-lasagna-deep-yard-litter/

To Vicky: This should be reported to the law and animal cruelty organizations. I know time has passed now, but if this keeps happening. Psychopaths start killing and torturing animals before moving on to more serious crimes.

Great article. I have a question: we have 14 hens (Black Stars) and they are about 25 weeks now. We are regularly getting between 9-12 eggs per day, which is fantastic!

We have, however, had 3 very strange eggs: one medium sized, mis-shapen, and brittle (and it had a gradient of colors, like it came out a section at a time); one very rough, small and brittle; and one teeny, like the size of a quarter (with no yolk).

Is this anything to be concerned about? Do you think we may have one sick hen, or is it just part of them learning to lay?

I found your article in my quest to figure out how to find which one is laying these odd ones.

Dave,

Thank you for your most intriguing question! It has been a week or so since you made the comment, and I’m wondering if anything has changed with the hen in question? I am wondering if a. the hen has some sort of illness that would contribute to her laying deformed eggs, or b. the hen was startled (and she may even be extremely sensitive to stimuli) at the time of her egg entering the uterus: this is when the first layers of calcium carbonate are deposited, and they can be squeezed and cracked in an irregular way if this happens, which could result in deformed eggs, too.

I’m hoping that the hen grew out of the condition and now everything’s hunky-dory? Could I ask that you report back?

Thanks!

Thanks for getting back to me. So, it seems as though the hen in question grew out of it. I wish there was a way of knowing which hen it was, but with so many, I don’t think it’s possible. No worries though. We now have a daily supply of 10-13 (and occasionally 14) beautiful and healthy eggs.

Keep up the good work… I really appreciate the interaction.

David, Hooray! That’s awesome that the problem righted itself. That’s the way it is, so often, with chicken and egg matters. Thankfully! Enjoy the eggs!

Hey Amy, I would like to thank you for the information on those hens that have stopped laying, I had eight that weren’t doing there job. I’ve been keeping chickens four years and didn’t know how to tell until your post. I know that seems like a long time not to tell but a dog got in my coop two years ago and killed 10 hens, now a new coop 28 hens well 20. Thank you again Bill; PS

UGH, Bill, that is frustrating! I’m sorry about your chicken loss. But a new coop is a great bonus! Glad my post was helpful.

Thisbwas a touching,yet very educational post. THANK YOU

You are welcome!

I have a , not even a year old yet . as far as I can tell she hasn’t laid since everyone started. Bad sceniero, something killed all but 2 around the time Hurricane Harvey hit. Now I have 2 . One lays and the other , who will not go in a coop but roosts in a tree each night isn’t laying that I can tell ( or find) . She also will not let you catch her. So I keep her around for the other hens company. I have looked every where I know ( hidden places) for signs of eggs. I also had ( not sure which one it was ) an egg eater when they started laying back in lat July 2017.

*ugh* Sounds like PTSD, Pat! I’d adopt a wait-and-see approach with that maverick hen. Maybe when the weather gets colder, she’ll decide that the coop is not such a bad place to be?

What happens if you have a hen(buckeyes), that are over a year old and they have never laid eggs and try to eat your other hens eggs?

Heather, sometimes . . . it’s easiest to just make soup. 🙂 Some hens will have bad habits and will not be rehabilitated!!

Thank you! Super helpful post. It helped me solve the mystery of whether my evil RIR was not laying or eating her eggs again. Alas, as demonstrated by her obviously large moist vent & wide bottom, she is eating her eggs. I was able to obviously see the difference by comparing her to another hen who has just molted and obviously is not yet laying again. I have been unable to break the RIR of her unsavory habit and she is almost three years old so she is destined for the stew pot.

It’s hard to make that decision sometimes, Laura, but it sounds like it may be the right one in this case.

I don’t have chickens yet (I raise quail because of zoning laws), but I fully intend to have some in the future (I’m moving soon.) I absolutely LOVE your ‘buy a different breed each year’ plan! I hadn’t ever thought of this, but I WILL be doing this. (I also am very glad to have an idea on how to figure out layers vs non layers. Great post!)

Thank you Pahla! I think that’s the easiest way to keep track of the age of your various hens, too!

Hi Amy,

Just finished reading your or some of your blog. It’s great… I saved it for future reference. Thanks for taking the time out of your busy life to share your gifts/talents/life with us.

Thank you, Jenny. My pleasure!

You mentioned “allowing” your genes to molt. How do you stop them ? I thought it was just something that happens naturally.

If you keep lights (on a timer) coming on in the coop during the winter (as described in this post http://vomitingchicken.com/hens-lay-eggs-winter-long/) you can “fool” the hens into thinking that it’s NOT time to molt. I’ve done this for as long as I’ve kept hens, and I have plenty of eggs year round, and the hens do not seem to mind!